A (Mostly) Non-Technical Introduction to IOTA's Mana

For India’s third national election in 1962, the National Physical Laboratory of India developed a proprietary violet ink formulated from silver nitrate, a light-sensitive compound common in photographic chemicals. Once a voter’s finger has been painted with this ink, any exposure to UV rays will leave an indelible mark that remains until the body generates an entirely new layer of skin. Because this form of voting authentication is produced by the sun itself, the simple act of showing one's hand proves whether one has voted or not. The election ink’s formula remains a closely guarded state secret.

This ingenious Sybil protection mechanism, which India still exports to countries across the world, relies on the fact that hands are hard to come by. If you can find an unmarked left hand, you can prove you have permission to vote. Through a simple certification process, every citizen gets one vote, and no one can vote twice without shedding some skin. Without some process of identification – ID cards, voter registration, election ink, e.g. – no voting system would be secure against double votes.

Every distributed ledger needs a solution to resolve conflicts and therefore needs to allocate a finite number of votes to network participants to prevent anyone from voting as many times as they please. In the Bitcoin network, anyone with a winning lottery ticket – the solution to a cryptographic puzzle defined by the protocol – has the right to vote on conflicts. Miners are more likely to win in proportion to the amount of electricity poured into computational work to solve the cryptographic puzzle, which is why the winning “lottery ticket” is called “proof of work” (PoW). Proof of work, like the unmarked hands of an Indian voter, demonstrates to every node in the network that a miner has an unexercised right to vote, which they can use to select the so-called longest chain. As a reward for doing this expensive proof-of-work, the miner, or consensus “leader,” receives fees and block rewards.

In contrast to proof of work-based systems, the IOTA protocol is a feeless and leaderless protocol: all network participants can propose ledger updates, validate transactions and participate in the resolution of conflicts in parallel. This design eliminates the distinction between users and miners. It is a fundamental departure from Bitcoin, and other PoW and PoS-based cryptocurrencies which elect a single leader to write updates to the chain and vote on conflicts, one block at a time.

Although IOTA is a leaderless protocol, like all DLTs, IOTA needs to allocate finite voting rights to network participants in a verifiable way to prevent anyone from voting more than their fair share.

Consensus mana

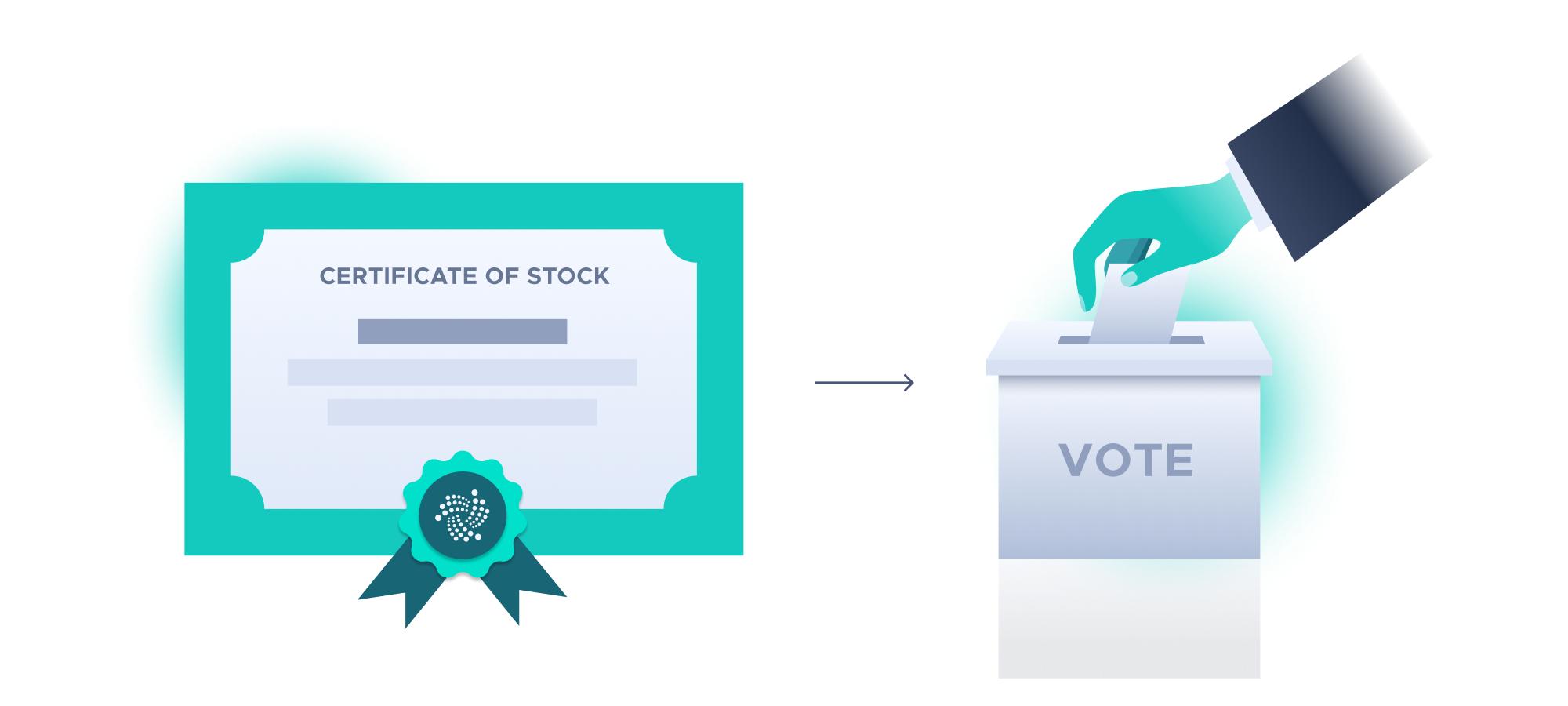

A share of common stock, sometimes called a voting share, is a store of value and possibly even a medium of exchange. It also serves as proof of the right to cast a vote in corporate board elections, which can be delegated to others through proxy voting. One share, one vote.

Similarly, IOTA uses the tokens native to the IOTA protocol to prove the right to vote on conflicts. This voting right, delegated proof of token ownership, is called consensus mana (cMana) in the IOTA protocol.

The idea of using token ownership as a way to allocate voting rights is not new. In 2011, a user on the BitcoinTalk message board, calling themself QuantumMechanic, proposed one of the first descriptions of the idea:

It’s worth noting that in QuantumMechanic’s definition, proof of stake refers to the idea of delegating votes to other nodes but has nothing to do with the concept of slashing – that is, revoking tokens from a user who votes in an obviously malicious way as a form of punishment – known from popular PoS-based cryptocurrencies.

Here, "stake" refers to having a stake in the network as a whole. As QuantumMechanic points out later in the post, users who hold a large stake in the network would have the incentive to preserve the value of the network by not voting in malicious ways. Proof Of Stake (PoS), in the simple form described here, is more of a delegated proof of token ownership, which represents shares in the value of the entire network. This simple form is quite similar to IOTA’s solution.

In IOTA’s feeless and leaderless design, cMana’s role in the system is different from that of PoS or PoW in a blockchain. In Nakamoto's consensus, PoS or PoW is used to elect a single block producer who gets the right to write to the ledger. If by chance more than one block producer is elected, then the next block producer will decide which of the two previously generated blocks to follow. Subsequently, the network will eventually follow the longest chain. In the context of Nakamoto consensus, Sybil protection is also part of a mechanism that enforces linear updates to the ledger. Because IOTA allows users to update the ledger in parallel, cMana is used to distribute voting rights across the entire network so that all cMana holders can participate directly in the consensus-finding process.

The Fast Probabilistic Consensus (FPC) is a voting protocol in which all network participants have the right to cast a vote on a conflict, weighted in proportion to the cMana they hold.

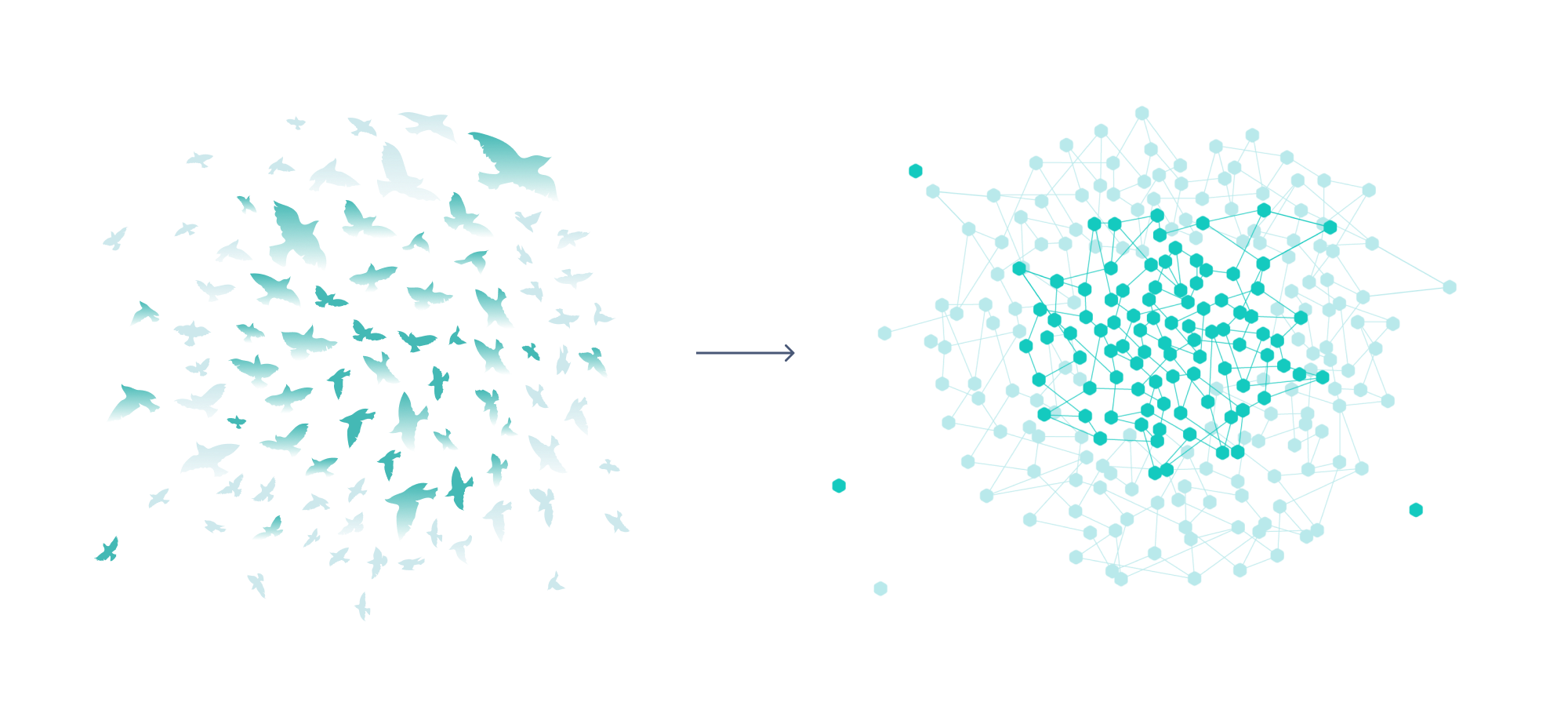

If two conflicting ledger updates enter the Tangle at roughly the same time, different nodes might have different perceptions of which one came first. They will use FPC to agree on which one to accept and include in the ledger. In simplified terms, nodes query the opinion of some randomly selected neighboring nodes and update their opinions by following the majority vote (weighted by cMana) of their neighbors. Through this simple behavior, the entire network comes to an agreement relatively quickly after a few rounds of voting, taking only a few seconds in case of such a conflict.

Similarly, flocks of starlings are believed to organize their collective behavior by individually following the behavior of six or seven neighboring birds in the flock. Every bird contributes to the organized behavior of the group, achieving a kind of leaderless consensus as to which direction to fly as a collective swarm. IOTA’s protocol behaves in a similar fashion to these kinds of organic systems.

Access mana

In the early days of the public telephone, users would have to present a special token minted by the phone company to an attendant that would let them use the phone for a few minutes. This interaction was eventually mechanized but proprietary telephone tokens persisted in the US until their metal was repurposed to produce shell casings during WWII.

Prepaid calling cards have supplanted the payphone in the 21st century, but the principle is still the same: they proved the right of access to a utility, in this case, the telephone company’s bandwidth.

This points to another important role mana plays in the IOTA protocol: access rights to a scarce resource. In addition to proving voting rights, mana also allocates access rights, called access mana (aMana). Access mana determines the permission to write updates to the ledger – or in plain words “send transactions”. The more aMana a user has, the more frequently they can utilize the network’s bandwidth to issue transactions.

In Nakamoto's consensus, writing a new block and voting on the longest chain are the same thing: a new block is automatically a single vote on which one is the longest chain. However, it is possible to distinguish at least logically between “access rights” and “voting rights”. PoW and PoS, in addition to allocating the right to vote to a single block producer, also allocate the right to change the ledger by publishing new information to the network. In the same way, IOTA distinguishes between consensus mana and access mana.

Because the IOTA protocol is leaderless, network users are free to issue transactions in parallel whenever they want. This means that if the network traffic reaches the physical limits of the hardware and infrastructure on which it operates, the role of access mana is to allocate network bandwidth to users in proportion to the tokens they hold. In general, those who have the biggest stake in the IOTA network, measured in terms of the tokens they hold, get the most access to the network in times of congestion.

In some respects, the IOTA network is like the utility cooperatives that proliferated in the US during the great depression to provide electricity (and now broadband) to rural communities. In IOTA, user-owners are granted access rights in proportion to the number of tokens (or shares) they own. Because there are no miners who demand fees, access rights are apportioned according to proof of ownership of the network itself. When you buy the IOTA token, you are effectively buying a portion of network capacity that you can allocate as you see fit for as long as you own the token.

IOTA’s mana is proof that a user who owns tokens has pledged their rights to a node. This proof gives a node the right to a vote in the consensus process and to send transactions through the network. The right to access (aMana) can even be delegated to, or revoked from anyone a user chooses to.

Mana is designed in such a way that anyone who has some stake in the network by owning tokens is granted rights in proportion to the stake they have. Because PoW and PoS systems only allow a single leader to update the ledger and participate in consensus, the resources of all the other network participants are wasted, to say nothing of the extreme energy waste that comes with PoW. IOTA’s concept of a fully decentralized ledger is one where all nodes collaboratively secure the network and issue transactions in parallel, utilizing the resources of all network participants in the most efficient and distributed way possible.

All systems, PoW, PoS, their numerous siblings and also IOTA’s FPC lead back to a slightly more philosophical question: where do these rights originate from? The answer to that is “trust”. The state or a corporation guarantees that the vote of a citizen or shareholder will be counted. A communication provider promises that a phone connection will be available.

Behind every right is some kind of promise, or guarantee, extended by an authority. This promise is usually expressed in an official declaration: a constitution, a set of bylaws, or a contract – statements that offer proof of the rights they extend.

It might be possible to say that these rights are nothing more than the promise itself. It is the fact that we trust that an authority has the power and will to fulfill its promise that gives rights their meaning. In a democracy in which no one trusts that their vote would be counted, the right to vote would be meaningless. Only trust gives the vote meaning.

In the case of a distributed ledger, the trusted authority is the codebase of the ledger itself. Relying on plenty of academic validation, and the durability of the protocol in real life, users voluntarily trust that the design and engineering of the ledger will distribute and enforce the rights which are promised by the code, all of which can and should be verified.

But even if a distributed ledger were perfectly engineered, if no one would agree to follow the honest behavior defined by the protocol, the whole system itself would be useless. This fact demonstrates that to some degree the trust in a digital ledger depends on the trust which people, “outside” the system, extend to it – a fact made obvious whenever a community chooses to fork a network through social coordination that happens “off-chain”.

After all, a distributed ledger is part of a human world, something like roads, electrical wires, or canals, which expand the possibilities of social life. There is no a priori reason why the trust that already exists outside of a ledger – the trust in certain institutions and people to behave honestly – cannot also be equally used to strengthen the agreements made among machines.

In ancient Athens, public officials, city council members, and jurors were selected in a lottery. Using a system of tokens and colored dice, a mechanical device called the kleroterion randomly elected citizens from each of the Athenian tribes. Because every citizen was considered equal, it was believed that the various civic powers of voting, of administering public offices, should be assigned through a random, mechanical process – something Aristotle considered to be the hallmark of democracy.

There is an interesting fusion of the mechanical and human aspects in this concept of democracy. A randomness generator guarantees some kind of fairness, but ultimately the system relies on trust extended to the elected citizens, people who would have known and dealt with each other in the city of Athens every day.

With tools like decentralized digital identities, it is entirely possible that in the future mana could form the basis of a more expansive reputation system that lets the valuable trust which is already extended to real people and real institutions interact with the trust we place in the behavior of the code which machines rely on today, and in the future.

The content of this article reflects the opinion of the IOTA Foundation but was written in large parts by IOTA community member @b0rg (Discord). Parts of the original article have been rephrased to reflect the opinion of the IOTA Foundation, in accordance and agreement with the original author. We would hereby like to express our sincerest gratitude for b0rg’s contribution. If you're interested in addressing an IOTA-related topic by writing an article for the IOTA Foundation yourself, feel free to reach out to Antonio Nardella on our Discord or talk to an X-Team-Simplify community member in the Discord channel (with the same name).

Follow us on our official channels for the latest updates:

IOTA: Discord | Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram | YouTube